How Alternative Media Provide The Crucial Critique Of The Mainstream

Media Lens | 20.01.2010 14:21 | Indymedia

“There will be no further need for newspapers or broadcasters to host debates and represent public opinion. The internet will let every citizen speak for themselves. The masses will seize the means of media production. We will witness an era of revolutionary change.” (

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/media/opinion/tim-luckhurst-demise-of-news-barons-is-just-a-marxist-fantasy-1856668.html)

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/media/opinion/tim-luckhurst-demise-of-news-barons-is-just-a-marxist-fantasy-1856668.html)

“... the public right to know [cannot] depend on the dictates of an individual's conflicted conscience. Such decisions should be guided by professional priorities and ethics. The fallacy rests on the delusion that private ownership by capitalists has damaged journalism. The facts suggest the opposite. Since the first American newspaper baron, James Gordon Bennett I, created the New York Herald, and his British disciple Alfred Harmsworth followed with Britain's Daily Mail, profit-driven ownership has liberated reporters.

“Before the barons, journalism readily succumbed to direct sponsorship by political parties. Impoverished publications were bullied by powerful litigants. They could not afford professional reporters and printed opinions not facts. Afterwards, while journalism has often exercised power without responsibility, it has done so in the name of a version of the public interest that is gloriously independent of the state.”

Luckhurst concluded:

“There is not yet a single one-size-fits-all model for profitable, professional journalism in the 21st century, but a powerful alliance of commerce, conscience and intellect is converging around the certainty that such journalism is essential if representative democracy is to endure.”

We responded to the article on January 5:

Dear Tim Luckhurst

Hope you're well. I enjoyed your article in the Independent, 'Demise of news barons is just a Marxist fantasy.' You write:

"In fact, the people who now predict the end of professional journalism's reign of sovereignty have attacked edited, fact-based reporting for decades."

Who are these Marxists predicting the end of the reign of professional journalism? And who are the people who "have attacked edited, fact-based reporting for decades"?

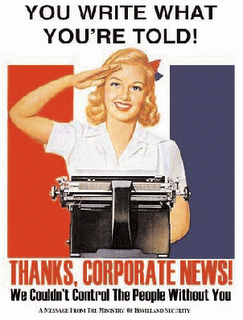

You write that "there is an elementary delusion behind the idea that amateurs can report accurately". But isn't there an elementary delusion behind the idea that corporate professionals can report accurately and honestly? After all, corporate media are tasked to report on a world dominated by allied giant corporations. These are the corporations on which newspapers like the Independent and Guardian depend for fully 75% of their revenues (from advertising). Isn't the conflict of interest obvious and important?

Best wishes

David Edwards

We received no reply. We wrote again, twice, and again received no answer.

We asked Richard Keeble, Professor of Journalism at the University of Lincoln, what he thought of Luckhurst’s piece. His reply was so interesting that we asked if he would expand it for a Guest Media Alert. This he has very kindly done. Sincere thanks to Richard for taking the trouble. We hope you enjoy his article.

Best wishes

The Editors - Media Lens

How Alternative Media Provide The Crucial Critique Of The Mainstream

By: Richard Keeble

I welcome Tim Luckhurst’s contribution to the debate over the future of journalism (“Demise of press barons is just a Marxist fantasy”, Independent, 4 January). But I disagree with him profoundly. Tim places far too much stress on the role of professional journalists in the current “crisis”. It is clearly important to work for radical, progressive change to the corporate media from within.

The closeness of the mainstream to dominant economic, cultural and ideological forces means that the mainstream largely functions to promote the interests of the military/industrial/political complex. Yet within advanced capitalist economies, the contradictions and complexities of corporate media have provided certain spaces for the progressive journalism of such excellent writers in the US, UK, France and India as John Langdon-Davies (1897-1971), Martha Gellhorn (1908-1998); George Orwell (1903-1950), I. F. Stone (1907-1989), James Cameron (1911-1985), Albert Camus (1913-1960), Phillip Knightley (born 1929), Seymour Hersh (1937), Susan George (1939), John Pilger (1939), Barbara Ehrenreich (1941), Peter Wilby (1944), Arundhati Roy (1960), George Monbiot (1963) and Naomi Klein (1970). Many of these have combined an involvement in the corporate media with regular contributions to the “alternative”, campaigning media.

Crucial Role Of Alternative Media

But most significantly Tim Luckhurst fails to acknowledge the crucial role of the non-corporate media in the development of progressive journalism. Historically, the alternative media have helped provide the basis on which an alternative, global, progressive public sphere has been built. For instance, John Hartley has highlighted the centrality of journalists such as Robespierre, Marat, Danton and Hébert to the French Revolution of the 1790s.

In the UK, in the first half of the 19th century a massively popular radical, unstamped (and hence illegal) press played a crucial role in the campaign for trade union rights and social and political reforms. In his seminal history of these early radical, “citizen” journalists, James Curran commented: “Unlike the institutionalised journalists of the later period they tended to see themselves as activists rather than as professionals. Indeed many of the paid correspondents of the Poor Man’s Guardian, Northern Star and early Reynolds News were also political organisers for the National Union of Working Classes or Chartist movement. They sought to describe and expose the dynamics of power and inequality rather than to report ‘hard news’ as a series of disconnected events. They saw themselves as class representatives rather than as disinterested intermediaries and attempted to establish a relationship of real reciprocity with their readers.”

Later on many feminists, suffragettes (such as Sylvia Pankhurst), trade unionists and anti-war activists were both radical journalists and political agitators.

Informal underground communication networks and newspapers (such as the Sowetan in the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa during the 1970s and 1980s) were crucial in the independent movements in Africa and India. Jonathan Neale, in his seminal study of the Vietnam War, identified around 300 anti-war newspapers in the armed services during the course of the conflict. Seymour Hersh’s exposure of the My Lai massacre of March 1968, (when US soldiers slaughtered up to 504 men, women and children) was first published by the alternative news agency, Despatch News Service.

From 1963 to 1983, the Bolivian miners’ radio stations highlighted the rights of workers. In Poland during the 1980s alternative publications of the Polish Roman Catholic Church and the samizdat publications of the Solidarity movement played crucial roles in the movement against the Soviet-backed government of the day. In Nicaragua during the 1980s and 1990s the Movement of Popular Correspondents produced reports by non-professional, voluntary reporters from poor rural area that were published in regional and national newspapers – and they helped inspire revolutionary education and political activities. In the 1990s, the Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan bravely reported on the abuse and execution of women under the Taliban producing audio cassettes, videos, a website and a magazine.

This century we have seen the use made of websites by reformist movements in Burma and more recently (with Twitter, Flickr, Facebook and YouTube) in Iran. Similarly, in Peru, in 2009, Indigenous activists used Twitter and YouTube to highlight human rights abuses as more than 50,000 Amazonians demonstrated and went on strike in protest over US-Peru trade laws which threatened to open up ancestral territories to exploitation by multinational companies.

Celebrating The Internet And Blogosphere

Today, the internet and the blogosphere provide enormous opportunities for the development of progressive journalism ideals in both the UK and globally. Stuart Allan, for instance, celebrates the bloggers and the “extraordinary contribution made by ordinary citizens offering their first hand reports, digital photographs, camcorder video footage, mobile telephone snapshots or audio clips”. A great deal of this “citizen journalism” (while challenging the professional monopoly of the journalistic field) actually feeds into mainstream media routines and thus reinforces the dominant news value system. The internet and blogosphere only become interesting when they serve to challenge the mainstream as crucial elements in progressive social and political movements.

Moreover, we need to follow John Hartley in making a radical transformation of journalism theory. We need as both academics and citizens to move away from the concept of the audience as a passive consumer of a professional product to seeing the audience as producers of their own (written or visual) media. Hartley even draws on Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which he suggests proclaims the radical utopian-liberal idea that everyone has the right not only to seek and receive but to “impart” (in other words communicate) information and ideas. If everyone, then, is a journalist then how can journalism be professed? “Journalism has transferred from a modern expert system to contemporary open innovation – from ‘one-to-many’ to ‘many to many’ communication.” Let us see how this redefinition of journalism can incorporate many different forms of media activity into the alternative public sphere.

Firstly, there is the role of radical, non-mainstream journalists. George Orwell (1903-1950) is best known as the author of Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) but he was also a distinguished progressive journalist who concentrated most of his writing on obscure, alternative journals of the Left – such Controversy, New Leader, Left Forum, Left News, Polemic, Progressive, Politics and Letters. From 1943 to 1947 he was literary editor of the leftist journal, Tribune, and through writing his regular “As I Please” column, instinctively developed a close relationship with his audience. This relationship was crucial to the flowering of Orwell’s journalistic imagination.

While he realised mainstream journalism was basically propaganda for wealthy newspaper proprietors, at Tribune he was engaging in the crucial political debate with people who mattered to him. They were an authentic audience compared with what Stuart Allan has called the “implied reader or imagined community of readers” of the mainstream media.

Today, in the United States, Alexander Cockburn and Jeffery St Clair produce Counterpunch, an alternative investigative website (www.counterpunch.org). Out of their writings come many publications. There’s also the excellent Middle East Report (www.merip.org), the Nation (www.thenation.com), Mother Jones (www.motherjones.com), Z Magazine (www.zcommunications.org/zmag), In These Times (www.inthesetimes.com); in Chennai, India, Frontline (www.frontlineonnet.com); in London there’s the investigative www.corporatewatch.org.

Coldtype.net in the UK brings together many of the writings by radical journalists, campaigners and academics (such as Felicity Arbuthnot and William Blum). Dahr Jamail is a freelance journalist reporting regularly from a critical peace perspective on the Middle East (seewww.dahrjamailiraq.com) while Democracy Now! is an alternative US radio station (with allied website and podcasts) run by Amy Goodman overtly committed to peace journalism.

Drawing Inspiration From Chomsky

Chris Atton argues that alternative media such as these often draw inspiration from Chomsky’s critique of the corporate myths of “balance” and “objectivity” and stresses, instead, their explicitly partisan character. Moreover, they seek “to invert the hierarchy of access” to the news by explicitly foregrounding the viewpoints of “ordinary” people (activists, protestors, local residents), citizens whose visibility in the mainstream media tends to be obscured by the presence of elite groups and individuals.

Then there’s the role of radical intellectuals such as the American historian Tom Engelhardt (www.tomdispatch.com). Other radical intellectuals prominent in the blogosphere have included the late Edward Said, Noam Chomsky, Norman Solomon, James Winter, Mark Curtis and the recently deceased African intellectual campaigner and journalist Tajudeen Abdul-Raheem. In the UK, activists David Edwards and David Cromwell edit the radical media monitoring site www.medialens.org which monitors the mainstream media from a radical Chomskyite/Buddhist perspective and in support of the global peace movement. Professor David Miller and William Dinan are part of the collective running www.spinwatch.org which critiques the PR industry from a radical, peace perspective.

Some research centres play important roles in the formation of an alternative global public sphere. For instance,

http://globalresearch.ca is the website of the Centre for Research and Globalisation, an independent research and media group based in Montreal. It carries excellent articles by Michel Chossudovsky, Professor of Economics at the University of Ottawa. Special subjects on the site include US war agenda, crimes against humanity, militarisation and WMD, poverty and social inequality, media disinformation and intelligence. There is also the website produced by the London-based Institute of Islamic Political Thought (www.ii-pt.com).

http://globalresearch.ca is the website of the Centre for Research and Globalisation, an independent research and media group based in Montreal. It carries excellent articles by Michel Chossudovsky, Professor of Economics at the University of Ottawa. Special subjects on the site include US war agenda, crimes against humanity, militarisation and WMD, poverty and social inequality, media disinformation and intelligence. There is also the website produced by the London-based Institute of Islamic Political Thought (www.ii-pt.com). Political activists often double as media activists. Take for instance IndyMedia (www.indymedia.org). It emerged during the “battle of Seattle” in 1999 when thousands of people took to the streets to protest against the World Trade Organisation and the impact of global free trade relations – and were met by armoured riot police. Violent clashes erupted with many injuries on both sides. In response 400 volunteers, rallying under the motto “Don’t hate the media: be the media”, created a site and a daily news sheet, the Blind Spot, which spelled out news of the demonstration from the perspective of the protestors. The site incorporated news, photographs, audio and video footage – and received 1.5 million hits in its first week. Today there are more than 150 independent media centres in around 45 countries over six continents. Their mission statement says:

"The Independent Media Centre is a network of collectively run media outlets for the creation of radical, accurate, and passionate tellings of the truth. We work out of a love and inspiration for people who continue to work for a better world, despite corporate media’s distortions and unwillingness to cover the efforts to free humanity."

In the UK, Peace News (for non-violent revolution), edited by author and political activist Milan Rai and Emily Johns, comes as both a hard copy magazine and a lively website (www.peacenews.info) combining analysis, cultural reviews and news of the extraordinarily brave activities of peace movement activities internationally. As its website stresses, it is “written and produced by and for activists, campaigners and radical academics from all over the world”. Not only does their content differ radically from the mainstream. In their collaborative, non-hierarchical structures and sourcing techniques alternative media operations challenge the conventions of mainstream organisational routines. Atton describes the alternative journalism of the British video magazine Undercurrents and Indymedia as “native reporting”. “Both privilege a journalism politicised through subjective testimony, through the subjects being represented by themselves.”

Fitwatch: Monitoring The Monitors

Members of Fit Watch, a protest group opposed to police forward intelligence teams (Fits), the units that monitor demonstrations and meetings, similarly combine political and media activism in their “sousveillance” – the latest buzzword for taking videos and photographs of police activities and then uploading them on to the web. They are part of a growing international media activist, protest movement. In Palestine, for instance, B’Tselem, the Israeli human rights group, gave video cameras to 160 citizens in the West Bank and Gaza and their shocking footage of abuses by Israeli settlers and troops was broadcast on the country’s television as well as internationally.

Citizens and campaigners in the UK and US who upload images of police surveillance or brutality on to YouTube or citizens who report on opposition movements via blogs, Twitter and websites in authoritarian societies such as China, Burma, Iran and Egypt can similarly be considered participants in the alternative media sphere. Commenting on the role of citizen blogs during the 2003 Iraq invasion, Stuart Allan stressed:

“... these emergent forms of journalism have the capacity to bring to bear alternative perspectives, contexts and ideological diversity to war reporting, providing users with the means to connect with distant voices otherwise being marginalised, if not silenced altogether, from across the globe.”

And for Atton, participatory, amateur media production contests the concentration of institutional and professional media power “and challenges the media monopoly on producing symbolic forms”.

Peace movement and international human rights organisations also produce excellent campaigning sites which can be viewed as forms of activist journalism. For instance,

http://ipb.org is the site of the International Peace Bureau founded in 1891 and Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1910. It currently has 282 member organisations in 70 countries. Or there is the Campaign for the Abolition of War (

http://ipb.org is the site of the International Peace Bureau founded in 1891 and Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1910. It currently has 282 member organisations in 70 countries. Or there is the Campaign for the Abolition of War ( http://www.abolishwar.org.uk). Formed in 2001 following the Hague Appeal for Peace in 1999, its founder president was Professor Sir Joseph Rotblat FRS, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate; while its founder chair was Bruce Kent. They work closely with the International Peace Bureau in Geneva for an end to arms sales, economic justice, a more equitable United Nations, political rights for persecuted minorities, a world peace force (instead of gunboat democracy), conflict prevention and education for peace in schools, colleges and the media.

http://www.abolishwar.org.uk). Formed in 2001 following the Hague Appeal for Peace in 1999, its founder president was Professor Sir Joseph Rotblat FRS, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate; while its founder chair was Bruce Kent. They work closely with the International Peace Bureau in Geneva for an end to arms sales, economic justice, a more equitable United Nations, political rights for persecuted minorities, a world peace force (instead of gunboat democracy), conflict prevention and education for peace in schools, colleges and the media. Exposing Human Rights Abuses

The organisation, Reprieve (www.reprieve.org.uk), campaigns on behalf of those often unlawfully detained by the US and UK in the “war on terror” and its director Clive Stafford Smith writes regular pieces for the “quality” press and the leftist New Statesman magazine, highlighting cases of abuse. For instance, on 10 August 2009, he wrote in the Guardian of three cases of government cover-ups. In the first, the government was refusing to hand over to the High Court details about the horrific torture of Binyam Mohamed (in Morocco and at the notorious US detention facility at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba) on the grounds that it would endanger future intelligence co-operation with the Americans.

In the second case, after the government admitted that two men had been taken for torture (“rendered” in the jargon) via the Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia, they were still refusing Reprieve’s requests for their names. And the final case involved cover-ups over Britain’s complicity in the renditions of prisoners from Iraq to abuse in Afghanistan. In the US, the American Civil Liberties Union (see www.aclu.org) has consistently campaigned to expose the human rights abuses which have accompanied the “war on terror” and produced a important series of reports on the issue.

Finally, Tim Luckhurst is wrong to suggest that advocates of alternative media are fired by “postmodern, Marxist fantasies”. Certainly my own writings on journalism and teaching for 25 years have not been based on any fantasies but rather grounded, in part, on a real desire to problematise the notion of professionalism. So, while clearly acknowledging the many achievements of progressive professional journalists I have always seen it as one of my crucial responsibilities as an educator to present students with an alternative to professionalism – drawing, indeed, for inspiration on a critical engagement with Marxism and postmodernism amongst a range of important concepts.

Richard Lance Keeble, Professor of Journalism at the University of Lincoln, is the joint editor of Peace Journalism, War and Conflict Resolution, shortly to be published by Peter Lang. David Edwards, of Media Lens, has a chapter titled “Normalising the unthinking: The media’s role in mass killing”. Richard Keeble’s chapter, “Peace journalism as political practice: A new, radical look at the theory”, expands on some of the ideas in this piece. John Pilger provides a Foreword.

Media Lens

Homepage:

http://www.medialens.org/alerts/index.php

Homepage:

http://www.medialens.org/alerts/index.php