Why the police riot? - part 11

Wesley Pritchard | 06.05.2009 21:49 | Analysis | Anti-militarism | Repression

This is part 11 of a series, for parts 1-10 see:

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/01/418797.html

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/01/418797.html  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/01/419998.html

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/01/419998.html  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/02/420982.html

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/02/420982.html  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/02/421761.html

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/02/421761.html  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/02/422077.html

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/02/422077.html  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/02/422683.html

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/02/422683.html  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/03/423404.html

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/03/423404.html  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/03/424220.html

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/03/424220.html  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/03/424776.html

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/03/424776.html  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/04/428093.html

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/04/428093.html  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/01//418801.pdf

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/01//418801.pdf  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/01//420000.pdf

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/01//420000.pdf  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/02//420984.pdf

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/02//420984.pdf  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/02//421762.pdf

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/02//421762.pdf  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/02//422079.pdf

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/02//422079.pdf  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/02//422685.pdf

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/02//422685.pdf  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/03//423405.pdf

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/03//423405.pdf  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/03//424222.pdf

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/03//424222.pdf  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/03//424817.pdf

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/03//424817.pdf  http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/04//428095.pdf

http://www.indymedia.org.uk/media/2009/04//428095.pdf

whythepoliceriot_part11

- application/pdf 498K

whythepoliceriot_part11

- application/pdf 498K

why_the_police_riot_complete

- application/pdf 3.3M

why_the_police_riot_complete

- application/pdf 3.3M

The TSG facilitating protest at Westminster Cathedral

The unchanging face of the FIT, police photographer Gavin Paul

Organisational diagram of Public Order Forward Planning Unit

-----------------------------------

APPENDIX A

Section 1: Government statement on rioting in Bristol, House of Commons, Wednesday 6 August 1980

Mr William Whitelaw: The review, which I announced in my statement of 28 April on the disturbances at Bristol [Cols. 971-972], has now been completed. In accordance with the undertaking I gave to publish the results, I have placed in the Library of the House a memorandum setting out the broad conclusions which have been reached following consultations with chief officers of police, the police staff associations and representatives of police authorities.

The review has concluded that it would be desirable neither in principle nor in practice to depart from the present broad approach adopted by the police for dealing with disorder. The successful maintenance of public order depends on the consent of those policed. The primary object of the police will continue to be to prevent and defuse disorder through maintaining and developing the close liaison between the police and the local community. At the same time, the public have a clear right to expect police arrangements to be effective if, nevertheless, disorder occurs. Much has been done in recent years to ensure that arrangements are effective, but the review has suggested a number of practical ways in which those arrangements could be improved. These include measures which will help to ensure that an appropriate number of officers can be deployed swiftly to any incident, with mutual aid between neighbouring forces where necessary, and that these officers are adequately equipped and trained.

My officials and Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Constabulary will, with chief officers of police and others concerned, proceed urgently with the further work that will be necessary to implement the conclusions of the review. I am confident that these provide a sound basis on which police will be able to carry out their duty to maintain order in a way which will continue to be acceptable to the great majority of people in this country.

[

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/written_answers/1980/aug/06/spontaneous-disorder ]

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/written_answers/1980/aug/06/spontaneous-disorder ] Section 2: Government statement on rioting in Bristol, House of Commons, Wednesday 6 August 1980

Introduction

1. In his statement to the House of Commons on 28 April 1980 on the disturbances at Bristol earlier that month, the Home Secretary announced that he was asking his officials and Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary, in conjunction with the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis and the Association of Chief Police Officers in England and Wales, to examine thoroughly and urgently the arrangements for handling spontaneous public disorder. He undertook to publish the results of the review.

2. The review has now been completed. In the course of it, the Home Office has also consulted the Police Superintendents’ Association of England and Wales, the Police Federation, the Association of County Councils and the Association of Metropolitan Authorities. This paper outlines the conclusions reached.

The basis of public order policing

3. The traditional belief that the police must have the consent of the community to do their job underpins the approach to handling disorder, as it does other aspects of police work. That is why the police in Britain have not, hitherto, adopted aggressive riot equipment, such as tear gas or water cannon, to handle disorder. Instead their approach has been to deploy relatively large numbers of officers in ordinary uniform, usually in the passive containment of a crowd. Where force has been used to restore order, this has been on the principle, which the law recognizes, that it should be the minimum which a reasonable man would judge necessary in all the circumstances.

4. Policing by consent and the principle of minimum force reflect not only a fundamental, humanitarian belief, but sound common sense. The effective preservation of order depends in the long term on the consent of the community. While the use of sophisticated riot equipment might be effective in quelling disorder in certain circumstances, it could also lead to the long term alienation of the public from the police. This in turn would make the task of the police in other areas of their work more difficult, quite apart from being undesirable in principle. Similar considerations would apply to the development of paramilitary riot squads within police forces or a paramilitary national reserve force. The police service itself would not welcome any developments along these lines.

5. At the same time, the police service must be able to keep order efficiently. The police have a duty to try to prevent criminal behaviour whatever its context. Present arrangements for maintaining order have to be made as effective as possible, within our broad police approach. Much has been achieved in recent years and the police are generally well able to maintain order where an event is known of in advance. But there is scope for improving arrangements to cope with disorder which breaks out suddenly.

Policing methods

6. The practical consequence of this basic approach is that the policing of public order in Britain depends on the availability of sizeable numbers of police, and the public order duties of a police force are one of the matters which are taken into account when its establishment is assessed. But forces must be in a position to deploy speedily an effective number of officers to an area when disorder occurs.

7. It might be argued that we should meet this need for rapid deployment, as some other countries have, by creating a mobile reserve of police on a national basis which could be called to any part of the country. But to do so would cut across the local basis of our policing arrangements and risk jeopardizing the relationship between police and public. There would also be problems in finding routine occupation for such a reserve body, and it would be a costly step. The review has therefore concluded that each force should develop suitable arrangements to enable it to respond speedily and effectively to disorder in its area, taking account both of its own resources and of those of neighbouring forces.

Speed of response

8. The key to these arrangements is the rapid assembly of an adequate number of officers in a short time at the place where they are needed. This may mean calling on officers from a number of sources: from patrol officers on duty; from a force support group or task force (where these exist); from officers in other divisions trained in public order duties whether on or off duty; from further partial or even total call-out of the force; and from other forces under mutual aid arrangements. The circumstances of each force vary so much that it would not be sensible to lay down a single and comprehensive national scheme for response plans. Each force will therefore be re-examining its own arrangements, setting up for this purpose a logistics planning team to ensure that a clearly defined command structure and operational plan can be put into effect speedily and efficiently to deal with an incident.

9. The immediate response to disorder is crucial. It will not necessarily always be appropriate to commit a large number of officers at the scene of disorder: it will be for the senior officer on the spot to judge what is the most sensible response to the particular circumstances. But to ensure that the police commander has an effective number of trained officers readily available to him, chief officers will set a minimum target for the number on which they can call immediately to deal with sudden disorder. This immediate response might be provided from members of force support groups or task forces or from individually assembled officers. Each chief officer will wish to decide what is most appropriate for his force. The setting up of a force support group where one does not exist at present is a matter for judgment in the light of the normal policing commitments of the force. Chief officers will be examining the case for such a group in reviewing their force’s response plans.

10. However the immediate response is provided, all the officers concerned will need to be organized to handle public disorder effectively. The most flexible structure will be units of one sergeant and ten constables.

11. In certain circumstances, it will be necessary for the immediate response to disorder to be further augmented with great speed, either from within the force or by mutual aid. Again, the circumstances of each force will vary and each force will set a target figure for the size of this secondary response. Further consideration will be given by chief officers collectively as to whether central guidance to forces on alert and call-out procedures can be formulated.

Mutual aid

12. The systems of mutual aid, under which each chief officer is able to call in case of need on other forces to provide him with aid, has worked well, particularly where an event can be planned for in advance.

13. Effective mutual aid arrangements are as essential in coping with spontaneous disorder as with pre-planned events, and they will be an integral part of the development of forces’ response plans and chief officers will consider invoking mutual aid at an early stage in an incident.

14. Each force needs to know the speed with which, and the extent to which, additional trained men can be made available by other forces. Arrangements for providing mutual aid will be reviewed by chief officers of police, in conjunction as necessary with the Home Office, to ensure that they enable a swift and flexible response to be made to disorder.

Transport and communications

15. If trained police officers are to be deployed swiftly to handle disorder, suitable vehicles and communications must be available. This is particularly important in the case of mutual aid. There may well be scope for improvement in existing arrangements here. How best these can be improved will be studied urgently by chief officers of police and the Home Office. Communications procedures as well as equipment will be examined.

Protective equipment

16. Police forces have responded to the rising incidence of violence at demonstrations in recent years by introducing a limited amount of personal protective equipment for police officers, chiefly shields and a stronger version of the traditional helmet. This is a step the police have taken with reluctance. However chief officers, and indeed the community as a whole, have a duty to ensure that police officers are adequately protected during disorderly incidents.

17. At the same time, any development which would tend to alter the traditional appearance of the British police officer and distance the police from the public is to be avoided. The Association of Chief Police Officers is conducting a review of protective equipment, in consultation with the Police Superintendents’ Association and the Police Federation and with assistance from the Police Scientific Development Branch of the Home Office. That review will consider how best officers can be protected without radically altering the image of the British police.

Training

18. Police officers at present receive training in the public order aspects of their duties, but the nature and extent of this varies. All officers need adequate training in crowd control, including training in the use of protective shields.

19. Every officer should receive basic public order training. This should include instruction in the psychology and problems of crowd behaviour, and the community relations aspects of public order policing. Additional training will need to be given to officers who may particularly be called on to police disorder or to supervise others during incidents. Further consideration will be given to the nature of this training and how it can best be provided.

20. In addition to formal training, forces will be arranging regular exercises to test response plans. There will be emphasis on the dissemination among forces of information about tactical planning and the handling of particular incidents.

[There is no para. 21.]

Public and community relations

22. This memorandum has already emphasized that the successful maintenance of public order depends on the consent of those police. Against that background, the effort put into establishing contact, trust and respect between the police and all sections of the community is a central consideration.

23. This review has been concerned with the handling of spontaneous disorder, and with the response to such disorder rather than how it might be prevented. But being able to respond swiftly and effectively to disorder is only part of the police approach to disorder: the primary objective must remain prevention, in its widest sense. In this context, it is the day-to-day work of careful and close community liaison by specialist officers and by those on the beat which can minimize future problems. The establishment of effective links with the organizers of protest events and with local community groups and leaders, is particularly important in this context. Where disorder does break out, the involvement of local officers in handling it can be important in helping to minimize any damage to community relations. Good relations with the press and other media can also help to prevent disorder and defuse tension. Chief officers will keep under close review the effectiveness of their arrangements in each of these respects.

24. The main object of public order policing will continue to be to prevent and defuse disorder and to maintain good relations with all sections of the community. Providing they are set firmly in that context, the conclusions reached in this review should enable the police to deal firmly with public disorder without incurring the penalties of fundamentally changing the concept and therefore the acceptability of the police service in this country.

Home Office,

Queen Anne’s Gate

6 August 1980

-----------------------------------

APPENDIX B

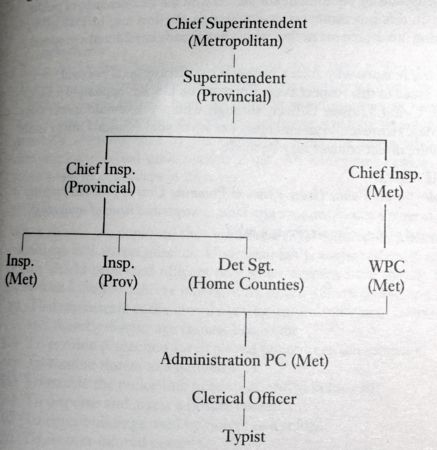

The Public Order Forward Planning Unit

The Public Order Forward Planning Unit is a national unit staffed by officers from a number of different forces answerable to the ACPO Sub-Committee on Public Order, and is formed thus:

[diagram]

The Unit has national responsibility for:

1. Discovery} methods }

Research } } for dealing with a breakdown in public order.

Evaluation} equipment }

2. Maintenance and amendments to the Public Order and Tactical Options Manual.

3. Circulating information and suggestions regarding new developments on behalf of the ACPO Public Order Sub-Committee.

4. Production and upkeep of a Public Order Equipment Manual.

The Unit is based at New Scotland Yard and for day-to-day administration purposes it operates as part of the A8 Branch of the Metropolitan Police. Contact can be made by telephoning (number).

Force Forward Planning Unit Liaison Officer

The Forward Planning Unit will act as a reference point in relation to public order research matters and Chief Officers have been advised to consult the Unit when contemplating any investigation or evaluation of new proposals or equipment connected with the maintenance of public order. In this way unnecessary duplication of effort may be avoided by referring one Force to another which has already considered a proposal,

or

by giving reasons why such a proposal has already been rejected.

To assist in this respect every Force in the UK has appointed a Force Public Order Liaison Officer, through whom you should direct your inquiries. However, in an emergency or when your Liaison Officer is not available, direct contact may be made.

REMEMBER

In order for the Public Order Forward Planning Unit to function properly it needs to receive and disseminate new ideas, concepts and items of equipment, for the benefit of the police service as a whole.

-----------------------------------

APPENDIX C

Extracts from the ACPO Public Order Manual

The following extracts were placed in the House of Commons library after being read into court during the Orgreave ‘riot’ trials:

LONG SHIELDS

1. Introduction

Long shields have been successfully used since 1977 in England and Wales to protect police officers in public order situations from attack by missiles. Having initially been regarded in some quarters as being an over-reactive and aggressive tactic, the deployment of long shields is now generally acknowledged by the public as being the norm when disorder has reached unacceptable levels. All forces now possess long shields and train officers in their use.

2. Objectives

When shields are deployed they tend to be regarded as provocative and encourage and attract missiles. Understandably, commanders generally deploy shield protected officers only when missiles have already been thrown and then to achieve one or more of the following objectives:

(a) To demonstrate to the crowd a strong presence of protected officers and thereby discourage riotous behaviour;

(b) To provide protection for deployed police lines under attack;

(c) To confine rioters to a defined area;

(d) To enable the police line to advance and gain ground;

(e) To disperse and arrest a hostile crowd;

(f) To enter buildings used by rioters as a refuge;

(g) To recover injured persons.

3. Formations

(a) The Shield Serial or PSU

The shield serial or PSU comprises one inspector, two sergeants and twenty constables.

(b) Shield serial

The shield ‘serial’ is a formation used by the Metropolitan Police. The serial is formed into three ‘five man shield units’, with a sergeant and six constables forming a reserve/arrest team. The second sergeant is a member of the centre ‘shield unit’ and the inspector (with a short shield) is in command. The centre shield man on each unit is the team leader. It is advisable that at least 2 serials work in conjunction. This formation has the advantage of a built in arrest team of a sergeant and six constables (in addition to the six ‘link men’ from the shield units) and these men are also readily available to replace injured shield carriers.

(c) Shield-protected PSU

The shield-protected PSU is divided into two ‘sections’ each of one sergeant and ten constables. The ‘sections’ are further divided into sub-sections of five constables each with a team leader. This formation has the advantage of providing four shield teams instead of three, but it has no reserve capacity.

(d) The Long Shield Sub-Section or Unit (Metropolitan)

The basic sub-section or unit comprises five members: three shield carriers and two link men. The three shield carriers are the front line and they link shields by the two outer shields interlocking behind the centre shield. The centre shield is pulled back and the outer shields pushed forward to maintain a locking seal. The two link men form a ‘rugby-type scrum’ behind the shields and knit the team together. This is a strong disciplined team with link men able to act as arresting officers. It does, however, tend to be slow moving and restricted in manoeuvrability.

4. Deleted from the copies.

5. Tactical manoeuvres

(a) A number of existing tactical manoeuvres are set out below designed to achieve the above stated objectives.

(b) The manoeuvres have been grouped according to the required objective.

(c) The manoeuvres stated can by no means be regarded as the only ones that exist, but they form the basis of others which can and have been developed to suit the local needs of forces according to manpower, equipment and other resources available. This is to be encouraged but it should always be remembered that the simplest tactics are often the most effective and need only minimum training and instructions.

6. Group One – display of strength

To provide protection for police officers. They are also an indication to a hostile crowd that police intend to enforce the law and have the potential to carry out that objective. In certain circumstances, the mere display of shields will be an indication to the less aggressive members of the crowd that it is time to disperse before the violence escalates.

7. Manoeuvre 1

(a) Brief description – show of force

(b) Detailed description

To use the ‘show of force’ to the greatest advantage, officers should make a formidable appearance. Officers should assemble at some point beyond the sight of the crowd. This point should be as near the crowd as practical to save time and to conserve energy, and yet far enough from the scene to ensure security. When the unit is in formation, it should be marched smartly into view at a reasonably safe distance from the crowd, thus giving the impression of being well organized and highly disciplined. When confronting the crowd the unit should be in the cordon formation (as described at 10(a) and 11(a)) with shields at their sides in a standby position. This show of force must convince the crowd that the police are determined to control the situation and are in a position to do so.

8. Group Two – protection for deployed officers

There is a strong school of thought that shields must always be used to advance the police on the crowd. That is, of course, the ultimate aim when there is serious disorder and peace must be restored. However, it is not always possible and certainly inadvisable if there is not sufficient police strength to achieve the objectives. Action precipitated without regard to the capabilities of the available manpower may result in serious injury to police and require the police commander to withdraw his forces.

9. With the above factors in mind shield units may be deployed statically to:

(a) Provide a controlled method of filter for non-hostile members of the crowd wishing to leave the area.

(b) Confine a hostile crowd to a geographical area advantageous to police strategy.

(c) Distract the attention of the crowd from unprotected officers – in other words to act literally as ‘Aunt Sally’s’ and draw fire.

(d) Act as a decoy and draw the crowd whilst other police units are strategically positioned.

(e) Afford protection to police officers who are operating using search lights, conducting searches.

(f) NOTE: This is X’ed through in the original: Protect officers engaged on other duties in searches, operating search lights, etc.

(f) Protect officers already deployed whilst reserves are brought in.

(g) Protect emergency services.

10. Manoeuvre 2

(a) Brief description – unit shield cordon

(b) Detailed description

Any number of long shield subsections are uniformly spaced across the road facing the hostile crowd in the position described at 3(d). There is a gap between each shield unit.

11. Manoeuvre 3

(a) Brief description – shield cordon base line

(b) Detailed description

The shield units form a cordon as described at 10(b). Instead of there being a gap between each subsection, they all link together to from a continuous shield line across the road with the link men in their normal position. On the command ‘open order’ the units split again into the position described at 10(b).

12. Manoeuvre 4

(a) Brief description – individual shield cordon

(b) Detailed description

Officers each carrying a long shield are uniformly spread across the road in line abreast either in ‘loose’ formation – a gap between each shield, or in ‘tight’ formation – the shields linked together.

13. Group Three – advancing the police line in order to gain ground and effect dispersal or arrest

Once the police commander has had time to consolidate his resources and to decided his strategy he may consider that it is necessary to advance the police line in stages to:

(a) Positions where it is tactically beneficial to him;

(b) Force a crowd back to facilitate the operation of other emergency services, i.e. fire brigade and ambulance;

(c) Secure and protect key buildings;

(d) Recover injured personnel;

(e) Give protection to arresting officers;

(f) Effect crowd dispersal.

14. Having determined and achieved his police line the commander must try to disperse the crowd and arrest offenders. It is difficult if not impossible for officers carrying long shields to make arrests, but they can effectively be used to disperse crowds and to provide protection for arrest squads of non-shield and short shield carrying officers.

15. To position arrest squads advantageously the commander will have to consider the terrain and bring unit forward under the protection of the shield serials in manoeuvres described in this group. These manoeuvres can also be used to bring in units around the flanks and behind the crowd so as to confine them in order to facilitate arrests.

16. Manoeuvre 5

(a) Brief description – advancing cordon

(b) Detailed description

The shields units as described at 10(a) are uniformly spaced in formation across the width of the road. Gaps are left between each unit, to facilitate return of stranded officers, etc., see 10(a). The units advance on the command in a controlled manner until they have achieved their objective and secured the ground. The back-up men in the unit and following reserves of short shield or non-shield carrying officers run forward when the opportunity arises and make arrests.

17. Manoeuvre 6

(a) Brief description – long shielded wedge

(b) Detailed description

A wedge is formed from 12 shield officers, with 2 shield officers at the head, standing close but not linking shields. The other shield officers of the unit stand to the rear and slightly to the left and right respectively. The sergeants position themselves at the end of either arm of the wedge. The Inspector takes up his command position in the wedge and is joined by the link men. They obtain their protection from the wedge. The wedge advances at speed through a shield cordon and into the crowd for an agreed distance (never more than 10 yards). At the agreed point the wedge thereby establishes a new secure line. Then, operating a split cordon movement, the 5-men shield sub-section pushes the crowd into side streets. In the event of the crowd running away from this advance, the link men and other reserves with or without short shields run through the line of long shields and make arrests. It is important however that the arrest squads do not advance more than about 20-30 yards to achieve their objectives.

18. Manoeuvre 7

(a) Brief description – free running line

(b) Detailed description

All officers are equipped with long shields and sufficient numbers are issued to fill the width of the road. The officers are spread uniformly so as to facilitate independent movement. Officers work in teams of 10 under the supervision of a sergeant who is positioned at the rear of the shield group. The line of shield officers advances on the crowd at a jogging pace. Within the capacity of the officers, the dressing being taken from a central point in the line, the supervising officer at the rear can dictate the speed of advance. The shields are held so that the bottom is tilted away from the carrier. The cordon is given a fixed objective, e.g. a road junction, but it should never be more than distance of 30-40 yards at a time. Arrest squads of short shield and/or non-shield carrying officers follow up and make arrests under the protection of the long shields.

SHORT SHIELDS

1. Introduction

Long shields have proved to be ideal for protecting officers against missiles, however they tend to be large and heavy and not really suitable for supervisors who whilst obviously needing some degree of protection don’t require it to the same degree as the front-line men. The short shield was therefore originally developed for use by supervising officers in charge of long shield units and has in that respect proved to be quite successful. Officers using long shields can’t move rapidly and find it difficult to make arrests. Disorderly crowds have recognized that face, in consequence of which long shields have tended to attract missiles. Obviously a method is needed to advance on the crowd at speed to make arrests but at the same time to give a degree of protection to the officers so deployed.

2. Objectives

When missiles are being thrown short shields can be effectively used to achieve one or more of the following objectives:

(a) To protect supervising officers in charge of long shield units and allow them to operate with those units without losing operational control;

(b) To provide protection for fast moving arrest squads;

(c) To provide protection for fast moving dispersal squads.

3. Tactical manoeuvres

(a) A number of tactical manoeuvres are set out below designed to achieve the above objectives;

(b) The manoeuvres have been grouped according to required objectives;

(c) The manoeuvres stated are not exhaustive but form the basis upon which others could be developed to satisfy local needs. Long-shield and short-shield units should be predetermined prior to deployment. Where possible both long and short shields should be carried in personnel carriers. Ideally, however, when actually deployed as a shield unit members of that unit should all carry only either long or short shields and not a combination of both. It is recognized that smaller forces may have insufficient reserves of manpower to permit such a degree of selection. Officers with short shields should not be deployed on defensive cordons and generally may need initial protection of long shields, water cannon or buildings, etc. When they are deployed it should be for a rapid action with very clear objectives.

Group 2 – Protection of four-man arrest squads

Manoeuvre 2

(a) Brief description – four-man arrest squads operating outside cover of long shield cordons

(b) Detailed description

Personnel are grouped into teams of 4, comprising 2 officers, with short shields in front and 2 back-up men. The teams take initial protection behind the cordons of long shields and on command will run forward towards an identifiable offender in an effort to arrest him. The two short-shield men protect the non-shield men whilst they make this arrest and take their prisoner back to the police lines. The team should not run forward more than 30 yards. They must stop after that distance and return behind the long-shield cordon cover area even if they have not made an arrest. Whilst the short-shield teams are making arrests the long-shield cordon should be moving forward in an effort either to pass the short shield teams to give them protection or to reduce the distance that the short-shield men have to return with their prisoners.

Manoeuvre 3

(a) Brief description – two-man arrest squads allowing one man to operate without a shield

(b) Detailed description

Officers working in pairs are deployed behind a cordon of long shields. One has a short shield with or without a baton and the other acts as the back-up. The back-up man holds on to the belt of the short shield man and on the given command they run forward into the crowd either through or around the flank of the long shields, or following up the ‘free running line’ (see Long Shields). The pairs run a maximum distance of 30 yards for the non-shield man to make an arrest under the protection of the short shield. In the meantime the long shield cordon advances in an effort either to pass the short-shield pairs to give them protection or to reduce the distance that the pairs have to return with prisoner.

Manoeuvre 4

(a) Brief description – four-man arrest squads operating with wedge formations

(b) Detailed description

Officers with short shields are positioned inside a wedge of long shields as described in Long Shields. Once the long shields have penetrated the crowd they will form into a shield cordon with the arrest teams of 2 short-shield and 2 non-shield carriers behind them. On the command the arrest team run either through or around the flank of the long shields to make arrests. The short shields should not advance more than about 20-30 yards and the long-shield cordon should advance to give added protection.

Manoeuvre 5

(a) Brief description – baton charge to disperse crowd

(b) Detailed description

All officers are issued with a short shield and short baton. The unit forms with 2 single files comprising 10 men each under the command of a sergeant, behind the long-shield cordon. When it is relatively safe to do so the files march forward either through or around the flanks of the long-shield cordons. On the command they form a cordon 2 deep across the road ensuring that the rear line have a clear view and path ahead of them. The cordon march forward on the crowd and if missiles are thrown, charge with batons drawn in an effort to disperse. Objectives must be given and the charge should not be for more than about 30 yards. Meantime the long-shield cordon should advance to gain ground and provide protection for retreating short-shield officers.

Manoeuvre 6

(a) Brief description – short-shield baton carrying team deployed into crowd

(b) Detailed description

Long-shield officers deployed into crowd and deployed across the road. Behind long-shields, units are deployed all with short and round shields and carrying batons. On the command the short-shield officers run forward either through or round the flanks of long-shields into the crowd for not more than 30 yards. They disperse the crowd and incapacitate missile throwers and ring leaders by striking in a controlled manner with batons about the arms, legs or torso so as not to cause serious injury. Immediately following the short-shield units the long-shield units advance quickly beyond the short-shields to provide additional protection. Link men from long-shield units move in and take prisoners.

Manoeuvre 7

(a) Brief description – short-shield teams deployed into crowd

(b) Detailed description

Officers carrying short-shields with or without batons are formed into 2 double 5-men files with a Sergeant at the back of each file and the Inspector between the 2 files. This unit will initially be protected by long shields or personnel carriers and on the command will run at the crowd in pairs to disperse and/or incapacitate. The long-shields will follow on to gain ground and give additional protection for arresting officers.

MOUNTED POLICE

Mounted branch officers may be employed in the public disorder context to achieve one or some of the following objectives:

(a) Confronting a hostile crowd with a display of strength to discourage riotous behaviour; this may be merely ‘within view’ or at ‘close quarters’ with the crowd;

(b) Applying pressure at close quarters to hold or ease back a solidly packed crowd, preserving the police line or gaining ground;

(c) Protecting buildings from a hostile crowd;

(d) Opening gaps in crowd or separating sections of the crowd by the measured weight of horses;

(e) Dispersing a crowd using impetus to create fear and a scatter effect;

(f) Dispersing a crowd using impetus and weight to physically push back a crowd;

(g) ‘Sweeping’ streets and parklands of mobile groups and individuals;

(h) Combining with other officers on foot (they employ varied tactics) to achieve any of the above objectives.

Group four – Crowd dispersal

When officers are deployed in close contact with crowds there is always the option of gradually pushing the crowds back thereby achieving a slow dispersal. The dispersal manoeuvres discussed below, however, provide for a more rapid dispersal based on fear created by the impetus of horses. A generalization can be made about dispersal tactics of this nature; that they are only a viable option when the hostile crowd has somewhere to disperse to rapidly. It would be quite inappropriate to use such a manoeuvre against a densely packed crowd.

Manoeuvre 10

(a) Brief description – Mounted officers advance on a crowd in a way indicating that they do not intend to stop.

(b) Detailed description

This manoeuvre can be applied whether there are foot police in close contact with the crowd in a ‘stand-off’ position or no foot police at all. The mounted police officers form in a double rank, line abreast facing the crowd and advance together at a smart pace (i.e. fast walk or steady trot) towards the crowd. Foot officers stand well aside to let them through and re-form behind following at the double. The horses stop at a predetermined spot, foot officers forming up behind. If missiles are thrown protected officers are brought through the horses, which are then in a position to repeat the manoeuvre.

Manoeuvre 11

Description

This manoeuvre is identical to number 10 except that the advance is made towards the crowd at a canter. The same considerations as regards foot police and halting the horses at a predetermined place apply.

Manoeuvre 12

Description

Combining a rapid advance of mounted police with foot police. Mounted officers with their horses formed in line abreast advance on the crowd followed by shield units jogging behind the mounted formation. When the horses make contact with the crowd the foot officers, with shields, are in a position to make any necessary arrests.

A warning to the crowd should always be given before adopting mounted dispersal tactics.

-----------------------------------

APPENDIX D

From the report of the Home Office working party on the police use of firearms, 3 February 1987.

GUIDELINES FOR THE POLICE ON THE ISSUE AND USE OF FIREARMS

Principles governing issue

Firearms are to be issued only where there is reason to believe that a police officer may have to face a person who is armed or otherwise so dangerous that he could not safely be restrained without the use of firearms; they may also be issued for protection purposes or for the destruction of dangerous animals.

Principles governing use

1. Firearms are to be fired by police officers only as a last resort when conventional methods have been tried and failed, or must, from the nature of the circumstances obtaining, be unlikely to succeed if tried. They may be fired, for example, when it is apparent that a police officer cannot achieve the lawful purpose of preventing loss, or further loss, of life by any other means.

[There is no para. 2.]

Authority to issue

3. Authority to issue firearms should be given by an officer of ACPO rank, save where a delay in getting in touch with such an officer could result in loss of life or serious injury, in which case a Chief Superintendent or Superintendent may authorize issue. In such circumstances an officer of ACPO rank should be informed as soon as possible. Special arrangements may apply where firearms are issued regularly for protection purposes, but these should be authorized by an officer of ACPO rank in the first instance.

Conditions of issue and use

4. The ACPO Manual of Guidance on the Police Use of Firearms is the single authoritative source of guidance on tactical and operational matters relating to the use of firearms by the police.

5. Firearms should be issued only to officers who have been trained and authorized in a particular class of weapon. Officers authorized to use firearms must attend regular refresher courses and those failing to do so or to reach the qualifying standard will lose their authorization and must not thereafter be issued with firearms. Authorized firearms officers must hold an authorization card showing the type(s) of weapon that may be issued to them. The authorization card must be produced before a weapon is issued and must always be carried when the officer is armed. The card holder’s signature in the issue register should be verified against the signature on the officer’s warrant card. The card should be issued without alteration and should have an expiry date.

6. Records of issue and operational use must be maintained. All occasions on which shots are fired by police officers other than to destroy animals must be thoroughly investigated by a senior officer and a full written report prepared.

Briefing

7. In any armed operation briefing by senior officers is of paramount importance and must include both authorized firearms officers and non-firearms personnel involved in the operation. Senior officers must stress the objective of the operation including specifically the individual responsibility of authorized firearms officers. Particular attention must be paid to the possible presence of innocent parties.

Use of minimum force

8. Nothing in these guide-lines affects the principle, to which Section 3 of the Criminal Law Act 1967 gives effect, that only such force as is reasonable in the circumstances may be used. The degree of force justified will vary according to the circumstances of each case. Responsibility for firing a weapon rests with the individual officer and a decision to do so may have to be justified in legal proceedings.

Warning

9. If it is reasonable to do so an oral warning is to be given before opening fire.

10. Urgent steps are to be taken to ensure that early medical attention is provided for any casualties.

Summary

11. A brief summary of the most important points for an individual officer is attached. It is suggested that this summary be placed on the reverse side of each authorization card so that officers will have it with them whenever they are armed.

AUTHORIZED FIREARMS OFFICERS

GUIDELINES ON USE OF MINIMUM FORCE

The Law

Section 3 of the Criminal Law Act 1967 reads:

A person may use such force as is reasonable in the circumstances in the prevention of crime, or in the effecting or assisting in the lawful arrest of offenders or suspected offenders or of persons unlawfully at large.

Strict reminder

A firearm is to be fired only as a last resort. Other methods must have been tried and failed, or must – because of the circumstances – be unlikely to succeed if tried. For example, a firearm may be fired when it is apparent that the police cannot achieve their lawful purpose of preventing loss, or further loss, of life by any other means. If it is reasonable to do so an oral warning is to be given before opening fire.

Individual responsibility

The responsibility for the use of the firearm is an individual decision which may have to be justified in legal proceedings.

REMEMBER THE LAW. REMEMBER YOUR TRAINING.

-----------------------------------

APPENDIX E

Extracts from ACPO guidance on The Use of Firearms in Public Order Situations, April 1990

Para 2: The most likely scenario involving the use of firearms during serious public disorder is where police are responding to it along recognised lines when one or more members of the crowd uses or threatens to use firearms, or are used from nearby premises. In either case, police support units (PSUs) with protective equipment would be ineffective.

Conventional tactical firearms teams which would usually operate within a strategy of isolation and containment would be seriously inhibited in dealing with a gunman sheltering within an unarmed crowd or in a building.

In either case firearms teams would also be at risk from missiles or other attack by the crowd and could be overwhelmed and disarmed.

Para 13: Whenever possible, in addition to specific police warnings given to armed offenders, every effort should be made to warn the crowd that firearms are being used.

Para 15: One of the greatest problems in a riot is identifying the location from where a shot is fired. It is probable the first indication of firearms being discharged at police will be when one or more officers are injured.

It is of the greatest importance that any information which might assist in identifying the gunman and the location from where shots are fired is collated and made immediately available to firearms teams on arrival.

Para 18: Armed response to a firearms threat could consist of one or more of the following:

1. Riflemen. Primarily used for counter-sniper response and observation, they should always be deployed in pairs and must have support to protect them from rioters.

2. Firearms teams. Possibly on foot but probably in armoured vehicles.

3. Baton rounds/CS gunners to be used in support of the firearms teams.

Para 19: Snipers/Observers: When intelligence is received that firearms may be used during pre-planned public events or spontaneous disorder, the deployment of firearms officers to support the usual police response should be considered. This could take the form of riflemen on high strategic points equipped with binoculars and radios. They would then be available to counter any threat and gather intelligence.

Care must be taken when positioning snipers and observers to ensure they are not vulnerable to attack from sections of the crowd. Where there is such a danger and the position is essential to the operation, additional protection must be provided.

Para 21: No hard and fast rule can be laid down when deciding on the nature of firearms teams support. Flexibility of response is essential. Such support will generally take two forms:

1. Force firearms teams equipped with conventional weapons and baton guns operating in support of PSUs and deployed either on the floor or in armoured landrovers;

2. Armed police support units. Self-sufficient units comprising a tactical firearms team, baton gunners, short-shield officers and dog handlers conveyed with their commanders, ideally in six armoured landrovers. Such units would replace foot personnel in sectors where a firearms threat or usage had occurred and are intended to provide the appropriate response to whatever threat the unit has encountered.

They can be divided into two armed PSU sections if required or, where resources are limited, may initially be formed only in section strength.

Para 22: Deploying tactical firearms officers in close support of PSUs. Firearms support in the form of specially trained officers in teams of four with their own supervisor are deployed at the rear and flanks of PSUs.

Under the direct control of the sector commander, firearms officers will have a communications network with the supervisor who has access to the firearms control officer who is in liaison with Gold (commander) and Silver (deputy commander) to report and advise on decisions.

Para 33: An armed suspect cornered, firing at police in a riot situation or holding hostages and demanding immediate police withdrawal may prevent established siege procedure being followed. There may be problems in maintaining a sterile area in which firearms teams can operate. Police may have no alternative but to resort to direct intervention and the use of firearms in order to protect life. Such operations are hazardous and in the case of buildings will require the appropriate authority for the use of distraction devices or CS.

Para 34: If a firearm is used from within a crowd following initial withdrawal of police and containment of the scene, the incident commander may well have to consider complete clearance of the riot area through the use of force, possibly using baton rounds, CS and armoured vehicles against the crowd in order to remove the firearms threat.

In the final analysis police may have no alternative but to use their firearms to protect life. In these difficult circumstances there will be a risk to bystanders from missed shots or over penetration of the target.

-----------------------------------

APPENDIX F

Extract from ‘Public Order and the Police’ by Kenneth Sloan, Police Review Publishing, 1979.

[Reproduced verbatim, all spelling and other errors are from the original]

INTRODUCTION TO POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS

Historically, the citizen’s wish to express his opinion, to demonstrate in favour of new reforms and to protest against society’s established order, has always been viewed as a cherished right and a safety valve. Changes in the law are more a result of political pressure than the reality of the actual situation and the majority of social and political changes during the last century have been hastened, if not caused, by protest groups. Modes of conflict, whether they are aimed at the police, the government, or the all-embracing “establishment”, stem from the frustrations and anger of people disillusioned by the traditional slow crawl towards social and economic reform. The procession, rally, sit-in, strike or work to rule, can have a more immediate and dramatic effect on public opinion, in an age where the mass media thrives on protest, than the tortoise-like process of airing grievances through official channels.

The vehicle of protest is not the prerogative of any particular group or political ideology and both the Left and the Right make use of the different modes of extra-parliamentary agitation. In a democratic society with complex and rapidly changing social needs, whose normal methods of progress involve seemingly lethargic bureaucratic and political deliberation, protest is not just a method of relieving frustration but can be a useful means of political criticism and direct involvement in decision making.

In a free society, protest takes two forms; general public discontent expressed via legitimate channels; and organised confrontation. The former is usually a prerequisite for the latter. The form of organised confrontation can be peaceful civil disobedience or outright revolution. Within a democracy a certain level of protest, civil disobedience and confrontation has to be tolerated, and in the majority of cases it is desirable if freedom of thought and expression are to be upheld.

A notable feature of organised protest since the beginning of the eighteenth century, is that calls for social and economic reform have always professed to be for the emancipation of the working class. The intellectual and organisational leadership has, however, with rare exceptions, emanated from the middle classes. The explanation for this may be found in the traditional working class adherence to the theory that some are born to lead, while others are born to be led. Since organised protest movements concerned with moral or environmental issues have been middle class motivated, it can be said that most protests take on significance only when better educated, potentially powerful people take the reins, and that protest is a manifestation of middle class dissatisfaction with the state of society.

Street demonstrations have become a familiar sight in recent years and, whereas they used to take the form of peaceful protest or dissent, are becoming increasingly violent. A demonstration can be an effective vehicle for recruiting new members to a political party; a means of publicity to alert the government, the press and the public to a cause; or merely an excuse for a rabble to have a free-for-all with an opposing party or the police. It is fortunate that many demonstrations attract only a few followers, but often a subject is so volatile that vast crowds are attracted to lend their support, as in the case of the anti-Vietnam, C.N.D. and National Front campaigns of recent years.

Where there is a political or potentially political issue, the most active participants are usually members of small extremist parties. They may act alone or under the umbrella structure of some particular cause, examples of which are the present day anti-fascist co-ordinating committees. It is frequently not the original demonstrators who cause any trouble, but the opposition, however well meaning both sides may be.

Since 1945 the left wing political parties have tried to influence the working classes by suggesting that the way to emancipation is to change society by overthrowing the government and abolishing the police, the capitalist system and all other established institutions. This change, it is claimed, would be followed by the reconstruction of a society based on socialism where the interests of the proletariat would be paramount. All of the parties that have been spawned during the last few decades are unanimous in their opposition to the present order of society, but their ideologies and the means of achieving that change differ quite radically. This division of ideas serves only to fragment the movement towards socialism and makes unity and the achieving of that objective just a dream.

The police officer is at the fore when it comes to the application of the law relating to the keeping of the peace for the majority and it is for him or her that the following chapters have been written. They attempt to explain the tenets of the main political doctrines and give brief biographies of some of the men who have influenced present political thinking. This section is only concerned with minority groups and a brief mention of the major political doctrines will not go amiss here as a basis for comparison.

The main ideologies in this country are, of course, conservatism, socialism and liberalism. Conservatism was based upon the teachings of Burke and Disraeli. It initially represented the aristocracy and landed gentry but their doctrines have been considerable modified since 1945 in order to appeal to lower income groups. On the Continent, conservatism is generally identified with nationalism and reluctance to accept social progress, as conservative parties have often been reactionary and anti-democratic. The British Conservative Party, however, owes its success to its ability to adapt to changing social needs. Until 1834, when the term “conservative was introduced, the party was known as the Tories.

Liberalism is a philosophy that believes in giving the greatest possible measure of freedom to the individual. It accepts some aspects of socialism but disapproves of state control or any other form of monopoly. The Liberals are the successors of the Whigs and, until the Labour Party came to power in 1922, were one of the two main political parties. The party went into decline and became almost defunct in the 1950s, but there has been a considerable revival in recent years.

Socialism is the idea of a society in which there are no social classes and where all live together under conditions of approximate social and economic equality. The term first came into use in the mid-nineteenth century, and has been associated with the names of Charles Kingsley, William Morris, John Burns and Keir Hardie. The development of trade unions accelerated socialism and the Labour Party was founded in 1900 as the Labour Representative Committee, to give the unions representation in Parliament. As a party they believe in a constitutional change to socialism by democratic means, with the gradual introduction of a welfare state, public ownership of industry and a redistribution of wealth.

A mention needs to be made of Communism here too, because Communists are divided among themselves into the followers of the doctrines of Marx, Trotsky and Mao Tse-Tung and are dealt with under these headings. Communism ideally refers to a society where all property belongs to the community and all are equal. Since no such society exists, present day usage of the term refers to the attempts to overthrow the capitalist system in order to achieve the ideal.

It should be remembered that new groups are springing up all the time and that policies and affiliations frequently change. It is therefore, not possible to give a completely accurate and comprehensive survey of all political organisations but only a guide. Even the terms “right” and “left” are occasionally confusing. They are used to identify the major divisions in political beliefs and originated during the French Revolution, when the more revolutionary members of the Assembly sat on the left of the speaker. Later “left” came to mean for the revolution and “right” against it. More recently the left has come to be identified with the working classes, while the right is seen to represent capitalism and the upholding of the existing social order.

MARXISM

Marxism is the doctrine of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, being the philosophical study of history, economic theory and social revolution on which modern communism is based. The starting point of philosophical Marxism is dialectical materialism, which is the art of investigating the truth by logical and persuasive argument, thereby exposing the defects in the reasoning of one’s opponents. Dialectics considers all phenomena as the natural outcome of evolution arising from the settlement of conflict and contradictions. The Marxist doctrine sees socialism developing out of class struggle and culminating in the creation of a classless society. This would be followed by a period of transition, known as the dictatorship of the proletariat, during which the material and economic conditions necessary to the evolution of communism would be constructed.

The Marxist subscribes to the view that wealth is the product of human labour, the value of any commodity being determined by the amount of labour needed to produce it. In a free enterprise market the economist sees the seller of labour receiving a set amount for his effort, while the Marxist sees the labour force producing more value than it is paid for. The difference between the labour cost and the price that the commodity sells for is profit which accrues to the owners of land and capital. This is seen as the accumulation of wealth by capitalists by appropriating the fruits of labour from the rightful owner, the worker.

In rejecting the view that the production of any commodity requires many factors and that each receives payment for that provided, the Marxist believes that labour is the only source of value and that land and excess profit are only “stored-up” labour. These opposing views manifest themselves in a class conflict between the owners of land and factories and the labour force; in other words between capitalism and communism.

The Marxist doctrine of economics also believes the capitalist system to be based on competition which forces the owners to use labour-saving machinery in their efforts to accumulate further wealth. In time the competitive element will force the weaker owners out of business and this will not only create a monopolistic situation but increase the exploitation of the labour force. As more labour-saving devices are used and more and more companies cease to exist, so the labour force will increase in size and the conditions of the working classes become intolerable. Marxists argue that the natural evolutionary step from the creation of the two extremes of wealth and poverty is revolution. They envisage the creation of a classless society by overthrowing the capitalist system and by the “expropriation of the expropriators”, i.e. the dispossessing of property by the workers from those alleged to have dispossessed it from them.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

A short biography of Marx and Engels will help in the understanding of the doctrine.

Karl Marx was born in 1818 at Trier, in what is now West Germany. He was one of seven children born to Jewish parents. His father was a lawyer, who had taken part in the pressures for constitution and reform in Prussia, and his mother was Dutch by birth and never mastered the German language. The young Marx studied law at Bonn University, philosophy and history at the University of Berlin, and later took up economics. In 1843, after a seven-year engagement, he married Jenny von Westphalen, the daughter of an aristocratic Prussian family, whose father was a state councillor and elder brother became Minister of the Interior. Shortly after the marriage Marx and his wife moved to Paris, where he became co-editor of a radical magazine, the “Franco-German Annals”. During this period he became acquainted with Friedrich Engels.

Engels was born in 1820, the son of wealthy textile manufacturer. He left Germany in 1842 to work in his father’s factory in Manchester, where he learned of the poverty and misery of the working class in England. This was an experience which had a profound and lasting effect on his life, and prompted him to write “The Conditions of the Working Class in England”. Marx was greatly impressed by this work and articles written by Engels for the “Franco-German Annals”. A close friendship developed between the two men and they decided to work together. Until 1869, while he worked in Manchester, Engels earned enough to support Marx as well as himself.

Marx was successively expelled from France, Belgium and Germany for his revolutionary activities. He took refuge in London with his family and spent most of the rest of his life studying and writing in the British Museum. Both Marx and Engels became involved with a society of emigrant German workers called first the “League of the Just” and later the “Communist League”. They were commissioned to prepare a programme for the movement which is now known as the “Communist Manifesto”. The manifesto asserted that history can be seen as a series of class struggles and that the final struggle would result in a victory for the proletariat and the irradication for all time of a society based on class. It recommended ten measures to be achieved as the necessary initial advancement towards communism, which ranged from a progressive income tax to free education for all children. The manifesto concludes with the now famous words, “The proletariat have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Working men of all countries unite”.

Twenty-five years of Marx’s life were taken up by the writing of his major work “Das Kapital”, which is an analysis of the economic laws which govern society. He only managed to publish the first volume himself before his death, and the other two were completed from his notes by his friend Engels. In the later years of his life Marx concerned himself with the social conditions in Russia and predicted a peoples’ revolution. In “Das Kapital” he also forecast the fall of all capitalist societies because of inherent faults in the system and maintained that the fall of capitalism must be the preparatory step towards the rise and triumph of socialism. He came, however, to have a thorough understanding of the British working classes and institutions, and believed that Britain was the only country that could achieve communism without having to be involved in a violent revolution.

Karl Marx died in 1883 and was buried in Highgate Cemetery in London. He still ranks as one of the most influential thinkers of modern times and his works are revered by many people as the working man’s bible. His detailed abstract philosophies are difficult to understand, yet it is true to say that during the last hundred years every social revolution has been influenced to some degree by his doctrines. Friedrich Engels died in 1895, not long after he had attended to the publication of “Das Kapital”.

The Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) is the largest and most experienced Marxist organisation active in Britain. It was formed in 1920 and from its inception saw its task as being the preparation of the way for the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism. Its critics on the left see the party as ineffectual and worn out, with little or no future; while those on the right view it as the strongest threat to democracy and the leading disruptive force in the labour field.

From the outset the party has been isolated from the working class and has failed to appeal to the electorate as a major alternative to the Labour, Conservative and Liberal Parties. Although the CPGB reached a record number of 56,000 members in 1942 the Trotskyist and Maoist organisations have poached so many of its younger members in recent years that the party is now an ageing shadow of its former self.

The CPGB manifesto is found in “The British Road to Socialism”, which was first published in 1951. It criticises the government’s policy of overseas military bases and overseas aid, the building of capitalist monopolies, and the repression of the working class by a few powerful individuals holding political and economic power. The party seeks to achieve the transition to socialism in a peaceful manner within the existing political framework of this country, but the party’s electoral record is far from impressive.

The party structure is in four parts. The congress is the highest authority and meets every two years to elect the executive, formulate policy and make recommendations for the future. The second level is the executive, a 42-member committee from whom the full time headquarters staff are selected; the executive also select the political committee of the party, which includes the general secretary, chairman, national organiser, industrial organiser, the editor of the “Morning Star”, and others to a total of 16. The third level of administration is the district committees, of which there are 19, some with full time organisers. Lastly there are local and factory branches which all members of the party are obliged to join. There are at present approximately a thousand such branches and the current membership of the CPGB is claimed to be in the region of 26,000.

The “Morning Star” is the party’s main organ of propaganda. In addition the party publishes a wide variety of magazines and pamphlets, including “Comment”, “Marxism Today” and “Labour Monthly”.

The Young Communist League

The Communist Party of Great Britain has, like most political parties realised the importance of attracting young people to its ranks. Since its early days the party has encouraged its own youth movement, the “Young Communist League”. The YCL’s main activities are concerned with young workers, but its members have always figured among the executives of the National Union of Students and there are currently over 50 student branches. The emergence of the more romantically popular Trotskyist, Maoist, Anarchist and Anti-Nazi groups has, however, weakened the membership of the YCL.

The Young Communist League publishes “Challenge”, a monthly newspaper; and an occasional discussion magazine, “Cogito”.

The New Communist Party

The New Communist Party was formed in 1977 by Sid French, the former district officer of the Communist Party of Great Britain. This group split with the CPGB on policy and ideological grounds. The issues involved the CPGB’s open criticism of the Soviet Union, particularly in relation to its treatment of dissidents, and the softening of the party line towards achieving socialism in Britain. The New Communist Party sees the Communist Party of Great Britain as surrendering to anti-Sovietism and trying to impose a policy of social democracy on the working class. The re-drafted manifesto of the CPGB is viewed by the NCP as a betrayal of Marxist doctrine. The supporters of the NCP consider that it is wrong to sacrifice such concepts as “dictatorship of the proletariat” and “democratic centralism” in an attempt to regain electoral popularity because it involves a weakening of Marxist purity.

TROTSKYISM

Trotskyism is the manifestation of communism based on the revolutionary doctrines of Leon Trotsky. It represents the Marxist school of thought in its purest form, as it existed prior to its debasement by the Stalinist regime. The writings of Trotsky impart original inspiration, and devotees are attracted by the intellectual aura surrounding the tenets of the Trotskyist school. The various groups following the Trotskyist doctrine accept the basis of the “Transitional Programme” which says that the inherent weakness of Capitalism will sooner or later act to produce a situation in which the working class will, of its own initiative, successfully overthrow the Capitalist system, which is seen as having outlived itself as a world system. At the same time socialism in the USSR is seen by the Trotskyist as a failure, therefore it is believed that the revolution must continue to combat the natural tendency of bureaucracy to rule from above.

The implications of direct democracy involve all workers in decisions of an economic and political nature. To this end an essential factor of the Trotskyist campaign is the indoctrination of the workers. Its ethos demands a sliding scale of wage rises, a reduction in working hours, workers’ control of the means of production and the destruction of capitalism. Key industries, vital to the national economy, are to be seized by the work force and to this end the establishment of workers’ self-defence groups and militia is seen as a necessary first step.

The British Trotskyist groups acknowledge that the task is a difficult one when faced with the labour movements apparent faith in the Labour Party and the Trade Union movement, with their belief that socialism can be achieved by a democratic process, thus avoiding insurrection. The task for the Trotskyist in this country is therefore, seen as twofold; the destruction of the capitalist system and the re-education of the British working class.

Finally Trotskyism entails internationalism; Stalin’s “Socialism in one country” is viewed as a sham and all socialists must continue the revolution until it is worldwide. Trotskyism advocates antinationalism, antibureaucracy and world-wide revolution to achieve a socialist system from national governments and party bureaucracy. Many dissident communists changed to Trotskyism after the suppression of the 1956 Hungarian uprising by the Soviet Union.

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky (whose real name was Lev Davidovich Bronstein), was born into a Jewish farming family in Yanovka, a village in the Ukraine, in 1879. He was exiled from Russia in 1900 for his activities in founding the pro-Marxist South Russian Workers’ Union. On Lenin’s invitation Trotsky went to London where he joined the team of Marxist propagandists grouped around the newspaper “Iskra”.

In 1905, travelling on a false passport, Trotsky returned to Russia and became engaged in writing pamphlets for the underground Bolshevik press in Kiev. During the first Russian Revolution he played a leading role both as an orator and organiser, for which he was exiled to Siberia. He fled Russia and settled in Vienna, where he founded the newspaper “Pravda” and devoted himself to journalistic and political activities.

On the outbreak of the February Revolution in 1917, Trotsky again returned to Russia and joined the Bolsheviks. In a role second only to Lenin, Trotsky prepared, organised and led the October insurrection, which finally brought the Bolsheviks to power. He was appointed Commissar for Foreign Affairs by the Communist Party Central Committee in the first communist government and later Commissar for War.

In 1923 he protested against Stalin’s suppression of democracy and the bureaucratisation of the party and sought to increase the process of industrialisation of the USSR. Trotsky and Stalin became engaged in a personal struggle for power, for there was a fundamental difference between the two. Stalin’s policy was “Socialism in one country” and an adherence to a rigid bureaucracy of the established revolution. Trotsky’s policy encompassed “The revolution in permanence” until the final annihilation of capitalism, and the abolition of bureaucracy.

Trotsky’s opposition to Stalin led to his being expelled from the central committee and later from membership of the Communist Party itself. He was finally exiled from the USSR in 1929 and took up residence in Mexico. In his absence he was convicted of conspiring to overthrow the Soviet government, by assassinating Stalin and other Soviet leaders; a charge which has always been refuted by his disciples.

1938 saw the proclamation by Trotsky of the Fourth International, a group of sympathetic revolutionary groups, who believed that the Soviet Union had reverted to conservatism and had betrayed the proletariat by becoming bureaucratic in nature and developing into an oligarchy whose own interests were primary. The Fourth International adopted a plan called “The Transitional Programme” which outlined the activities that a Trotskyist group ought to persue prior to the final insurrection.

The following year he founded the International Communist League, a revolutionary group subscribing to the Marxist-Leninist theory and advocating the continuance of revolutionary activities on a world-wide basis. In May 1940 an attempt by Stalin’s agents to assassinate Trotsky failed, but in August of the same year a G.P.U. agent, posing as a follower, succeeded in killing him by driving a pick axe through his brain. Although inferior to Lenin as a philosopher and Marxist theorist, and to Stalin as a politician, Leon Trotsky is acknowledged by many to be the greatest revolutionary man of action of the twentieth century. He saw Lenin as the saviour of the USSR and Stalin as the betrayer.

The Socialist Workers’ Party

This Trotskyist group was formerly called the International Socialists and renamed the Socialist Workers’ Party on 1977. Although Trotskyist in its source and containing many devotees in its membership (including its executive), the group tries to steer an independent line. However, in common with many groups, its main struggle has not been the preparation for any mass working class insurrection so much as one of survival. Since the loss of industrial impetus following the failing of a call for a general strike in 1974, the party has switched its focus of attention to other issues, particularly the anti-racist campaign. It has created its own industrial section, student movement and propaganda machine, and has established itself as a good exponent of the single issue campaign. In an effort to infiltrate key major industries the SWP has set up Rank and File Groups in those industries, professions and unions where it has some support. The party propaganda machine publishes newspapers aimed at attracting support within these sectors of employment such as, “Rank and File Teacher”, “Carworker”, “Collier”, “Redder Tape” and “Electrician Special”. These newspapers vary in circulation figures as output frequency is dependent on the amount of activity within a particular industry at any given time. The main organ of the party is however a weekly newspaper, “Socialist Worker”. At one time the SWP could be regarded as academic and student orientated, but during the seventies the base had broadened to include militants within major industries; a move not only welcomed by the executive but positively encouraged. The leaders of the party consider the involvement of members in trade union and trades council activities as being of paramount importance in their struggle to establish the SWP as the true revolutionary party.

They have recently also become involved in stirring up dissent in schools.

The policies of the SWP stem from an Executive Committee of nine members elected at the annual conference. The second level of the party’s hierarchy is a forty-strong National Committee which meets monthly to discuss activities and policy, and to hear reports from the nine regional units which cover the whole country. Below the regional units, the grass roots of the party is located in local and factory branches. The SWP claim that there are more than 150 of these units.

Leading lights in the party include the founder member Tony Cliff (Yagel Gluckstein), full time organisers Steve Jeffreys and John Deason and journalist Paul Foot.