Venezuela - World Social Forum and work in the barrios

Jenny Fortune | 07.05.2006 15:25 | WSF 2006 | Analysis | Culture | Social Struggles | Sheffield | World

This January a delegation from the London-based Venezuela Information centre went to the World Social Forum in Caracas, Venezuela. There were representatives from Student Unions, the Greater London Authority, the Green Party, Trade Unions, journalists and academics. The majority of the group came from the north of the UK.

It's not easy to get an authoritative understanding of what's going on in 2 weeks, so I will give a fairly impressionistic view of my time there.

Firstly, Caracas is the first city in a southern hemisphere country that I have been in ( apart from Havana). I was breathtaken ( literally) with scale and noise and pollution. It sits in a massive long and deep valley between two mountain ranges, with the Caribbean ocean on the other side of one. The mountains are covered in jungle which spills down the sides into the city.

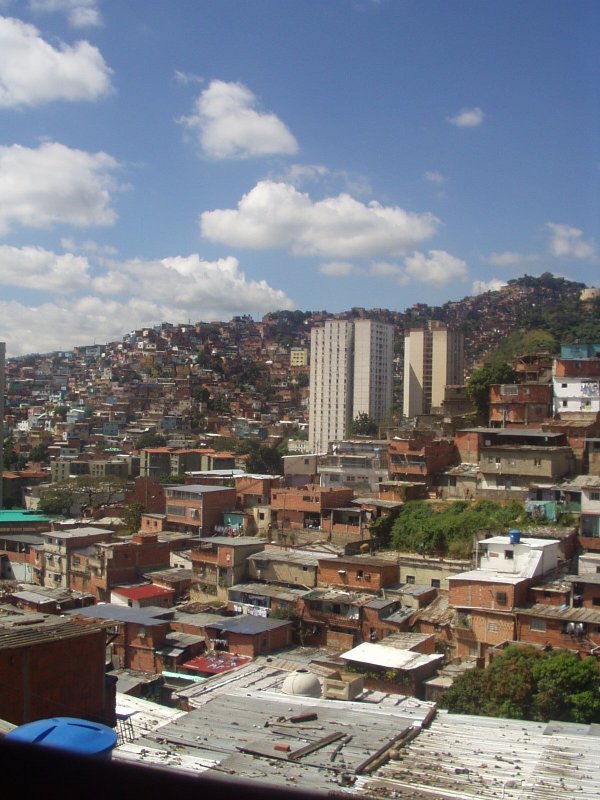

Also the shanty towns, housing a population of around 5.5 million people, cover the sides of the mountains, cascading perilously down towards the centre of the city. The city itself is a modern, Manhattan-like environment - thousands of striking steel, glass and concrete skyscrapers competing with the awesome scale of the mountains.

My first experience was of the World Social Forum, centred around the national theatre complex, a massive building reminiscent of the Mayan pyramid temples.

The Venezuelan government had given over whole main streets and national buildings and parks to house the thousands of people arriving from all over Latin-America and North-America.

The inaugural demonstration was made up of groups carrying beautiful banner after banner

- grass roots organisations such as hundreds of women's organisations for peace and anti-war and violence, black North-Americans from New Orleans, peasants from land co-operative movements,

- grass roots organisations such as hundreds of women's organisations for peace and anti-war and violence, black North-Americans from New Orleans, peasants from land co-operative movements,

workers from occupied factories - and all headed by hundreds of Cubans, the most tightly knit group I have ever seen on a demonstration.

workers from occupied factories - and all headed by hundreds of Cubans, the most tightly knit group I have ever seen on a demonstration.

The forum itself was quite a feat of organisation - and I'm still pondering over what it achieved. The organising principles, I believe, were:

- giving political autonomy to the movements and groups who came to the forum

- allowing all participants to express themselves freely

and I think this was achieved.

There were over two thousand forums, meetings and workshops organised over 4 days. They were grouped into 8 organising themes of:

- Human Rights

- Feminism

- Globalisation

- Arts, music, culture

- War and Peace

- The media

- Environmental Justice

- Organised labour and workers' rights.

The stated aim was to make connections and develop common approaches and solutions to problems.

It was bewilderingly difficult to decide which to go to, many had overlapping subjects and it seemed they should have joined together.

The meetings about land and agrarian reform seemed to be the biggest, and the one I went to was definitely the most exciting and inspiring of any of the sessions I attended, with organised groups of peasants from all over Latin-America having intense political debate with ageing agrarian economists from Spain and Portugal, taking lessons from the Spanish civil war and the Portuguese revolution of the seventies - wow! There were even some of the beautiful songs from the Portuguese revolution being sung.

I went to some disappointing women's meetings, where there were 'apparatchiks' from Cuba who seemed to be boredly mouthing the same old tired phrases about women's solidarity, and most of the women seemed to be working for NGO's. i.e.: no grass roots activists. But it was great to see these women, mainly black and indigenous, proud and strong and organising.

I also went to some disappointing meetings about housing and urban development, where the issues were so varied and complex that people from different struggles seemed to have trouble understanding each other or drawing common lessons.

I went to some stunning 'forums' in the evenings, with impressive speakers such as Samir Amin, the Egyptian economist, calling for Latin-America to lead the struggle against US imperialism; Rosa Guaman, indigenous rights leader in Ecuador, stating that the Cubans show us that 'another world is possible' by the way they are exchanging human skills of health care and education for Venezuelan oil. And then Hugo Chavez at the grand finale breaking into song - and he has got a pretty voice! a kind of light baritone.

It was exciting to meet all kinds of people from all over Latin-America,

and there was no doubt that there was an atmosphere of hope and activism and also great openness and warmth to each other. The final session was opened by one of the liberation theology priests asking us all to hug our neighbours - mine were North American, Brazilian and Columbian, and they all gave great hugs!

So, there is all that and a lot more. There is of course the issue of who can afford to get to these social forums, and there's no doubt there were a great deal of revolutionary 'tourists' such as myself. I think I will raise money to send grass roots Latin-American women activists to the next one.

The barrios, the CTU's and women's activity

The main reason why I was in Venezuela was to carry out research on the part women are playing in the re-development of the barrios.

Attempts to make contact with appropriate people through diplomatic contacts proved useless, and the most effective method proved to be walking up to one of the stalls which the ' Mission Habitat' had set up in the street during the WSF to enable Venezuelan's to directly access housing services.

It also proved to be the way I directly accessed services. The next day I had a meeting with Isaloren Quintero, head of the 'Comites de Tierras Urbanas',' CTU's, (Urban Land Committees) a young woman in her mid-twenties wearing a red headscarf,

and Quintin Aular, a 60 year old architect wearing a black beret.

These two were working in the huge steel and glass skyscraper now housing 'Mission Habitat', the new government housing organisation set up to by-pass the corruption and inefficiency of the previous housing Ministry (a complicated situation which I won't go into here).

They gave us the background to what is going on in the barrios and arranged for us to meet people in the barrios at many different levels.

The form of the barrios is such that they are dangerous places to live in - they are self-built dwellings on occupied land stacked perilously on top of each other on the sides of the mountains, with illegal electricity cables looped casually all over the place and open running sewers.

The main form of access is by flights of steep steps, requiring everything from water to bags of cement to be carried by back and legs.

But they are also dynamic and exciting places; especially so now cash is flowing in directly to the community to control their own development. 15% of the Venezuelan population ( i.e.: about 5.5 million) lives in barrios, or their inferior cousin, 'ranchos' (even more perilous and transitory buildings).

Below, Barrio 'Buzual'.

By Presidential decree 1,666 in 2002, Venezuelans gained the right to title to the land and house which they had occupied if they could prove occupation. According to women we met in the barrios, this means that about 70% of the titles are going to women, as the Latin-american/Caribbean family structure of women-headed households predominates. This is unprecedented on a world scale. The current task is to re-develop every single dwelling in the barrios, a task which they aim to complete within the next 20 years!

The main form of organisation is the CTU.

These are representative neighbourhood committees. In order to gain title to their house, barrios residents have to organise themselves into groups of 120-150 dwellings, and these comprise the CTU's. Meetings are open to all, and activists who take most responsibility are from that group of houses and work voluntarily. The meetings debate and take decisions about most things concerning the community - deciding on access to the Missions such as Literacy, Healthcare, food for the unemployed and homeless, special care for excluded women and children.

Perhaps most significant of all at the moment are the construction co-operatives. These are comprised of about 12 workers each, and they are engaged in re-building the houses in the barrios one by one. The barrio we spent most time in was Barrio Buzual.

The CTU decides the order of priority for re-building the houses, the priority going to those most in danger of collapse and the most over-crowded or vulnerable.

The CTU we spent time with had 6 construction co-operatives, where women were the majority.

The construction co-operatives work side by side with the employees of construction companies who carry out the skilled work, and the co-operative members seem to work as labourers, carry and mixing cement etc. A lot of the women seemed to act as a kind of quality control, but told us they had no training.

My impression was that many of the skilled men came from all over Latin-America and the Caribbean, attracted by the secure employment and reasonable working conditions.

( Anecdotal knowledge is that many of the heads of military made redundant in the re-organisation over the last years, have started up construction companies. No doubt they are making a nice profit at the moment, as construction is the main new economic activity taking place)

A meeting later on with the head of INCE ( Colleges for training, skills and social inclusion) confirmed that they are setting up new technical skills colleges on a grand scale, both in the barrios and the rural areas. They aim particularly to initiate courses in construction skills, but it hasn't occurred to them that women may need extra support to enter these courses.

Quality of the new housing

Each CTU has a number of engineers, architects and surveyors working with them to re-design the housing.

There does not seem to be a shortage of these, and I encountered, interestingly, quite a few women engineers and architects from different Latin-American countries working there and in Mission Habitat. (In fact, all the barrios we went to did seem to be swarming with professional workers of all types.) Below, a sociologist and an engineer.

A Clerk of Works and an architect:

The houses are being re-built with deep concrete foundations, strong steel frames and infill breezeblock walls with corrugated steel roofs.

I was disappointed by the lack of attention to sustainable materials, and particularly the lack of attention to ventilation and insulation in that tropical climate, and extremely poor access and layout design. I got the idea that the priority is to get the barrios re-built as quickly as possible in order to satisfy the people's demand, and not enough attention is being paid to long-term viability and sustainability. This impression was confirmed by architects and planners (1) from the University of Caracas, and also the self-styled 'Caracas Urban Think Tank' (2). But also they had their own axe to grind, as there is no doubt that many of these professionals have been sidestepped by the new and 'dynamic' Mission Habitat.

There has been an ongoing complaint from the people of the barrios that CAMEBA ( the government body responsible for Urban Planning and Regeneration) had spent about thirty years doing very little, and this was associated with the corruption of the Housing Ministry ( Ministerio de Vivienda) which we were told was in the habit of diverting funds to their own personal construction projects.

We had a meeting with the head of the Co-operatives, who gave us impressive figures on the amount of re-construction of barrios and ranchos. He showed us brochures and videos which demonstrated that the main form of renewal is by major construction companies which use pattern book designs, i.e.: a choice of three designs, identical materials. The unskilled labour is mainly carried out by women who get involved in the construction of their own homes. Many questions here, but when the priority is to re-build on a massive scale, is it possible to do things in a sustainable way? When I asked him whether they intend to train women in construction skills, he replied that women don't like to do heavy jobs (!) - sadly similar to what we hear here.

Finally, I had a meeting with Nora Castaneda, president of the Banmujer ( women's bank) which finances women's development projects. She affirmed that they would like to run projects training women in construction skills and that they would be able to develop this with the institutions we had talked to so far, i.e.; Mission Habitat, the Co-operatives and INCE, and asked me to submit proposals.

Jenny Fortune

Comments

Display the following comment